Excerpt From:

The Blacksmith’s Shop

“The chief quartermaster will direct that a set of blacksmith tools complete, and some iron, be sent to Fort Sumner for the use of the Navajos. Tell them to go to work at once and make adobes to build the shop. You select the site near the post, and have the shop made long enough to have a forge in each end.”

—Captain Ben Cutler, Fort Sumner, New Mexico, August 1864

It’s not clear when the forgeries began, but in early 1865, soldiers working in Fort Sumner’s commissary discovered that their ration tickets had been altered, allowing for more food than originally authorized. Other tickets simply disappeared from circulation.

“These tickets,” army surgeon George Gwyther recalled a few years later, “at first made of stout card-board, were so often willfully lost, or the writing on them so skillfully forged, that stamped metal slips were substituted.”

Of course, the same Diné headman who knew how to write like a Bilagáana also knew how to work metal. And now he had access to a complete set of blacksmith tools courtesy of the U.S. Army. Gwyther reported that “in short time it was found that their ingenuity had enabled them to make dies and forge the impressions successfully.”

So successfully, in fact, that no one could tell the difference. The soldiers didn’t know they’d been conned until they counted the tin tickets they’d collected and discovered they’d taken in more than they’d handed out. After one such tally in May 1865, Captain Henry Bristol reported to the post adjutant:

“In conclusion, I would state that the number of spurious tickets are increasing, and they are so handsomely executed as to be indistinguishable. Three hundred of these tickets are among the genuines and are so much alike and the same that Mr. Edgar is unable to throw them out.”

All told, the prisoners counterfeited more than three thousand ration tickets that year. They also successfully duplicated three hundred of Carleton’s military passports, which granted anyone who slipped out of Bosque Redondo safe passage through New Mexico.

The fraudulent passports may explain how Barboncito, after he was captured in Canyon de Chelly, managed to escape from Bosque Redondo in July 1865 and elude Union soldiers for more than a year. He finally returned of his own accord in November 1866, bringing with him a few families on the edge of starvation.

Similarly, Manuelito not only managed to evade capture for three years but also surreptitiously visited Bosque Redondo at least once. The most wanted man in the territory proved impossible to catch. He finally gave himself up in September 1866, after he was shot in the forearm in a skirmish with Hopi warriors and his followers lost the will to fight.

The army eventually put an end to ration ticket counterfeiting by ordering brass tokens shipped in from a federal mint, each about the size of a half dollar—impossible to duplicate under the conditions of the camp. A photograph taken at Bosque Redondo shows more than a dozen Diné men, seated on the ground, apparently under guard. It’s captioned, “Navajo chiefs accused of counterfeiting ration tickets at Bosque Redondo, Fort Sumner, New Mexico.” Yet there’s no record of charges being filed.

Delgadito was the obvious suspect. Punishing him, however, was another matter. The general had turned Delgadito into the symbol of the supposed subjugation of the Navajo; how could Carleton admit that he’d been duped by his prisoner?

By the time the counterfeiting operation was uncovered, Carleton could not afford another scandal. His critics were growing by the month. The previous December, the Santa Fe Weekly New Mexican accused him of participating in the slave trade he’d forbidden. Under a headline declaring, “Carleton Gives Away One of His ‘Pets,’” the paper reported:

“Indian in his possession, but I have lately learned that General Carleton Everybody is aware and knows that no one is allowed to have a Navajo presented a little Navajoe girl to a sutler, 3 or 4 months ago.…I’ve not the slightest ill-feeling towards the sutler (who is a gentleman), but I could merely call the attention of the people of New Mexico to the fact that while many of them have been compelled to give up the Indians whom they had for many years, and who were perfectly contented with their situation, General Carleton, as a matter of economy, keeps them on hand for presents and gifts.”

In Washington, there were complaints about how much Bosque Redondo cost and questions about the treatment of prisoners. Carleton’s superiors received reports of one deprivation after another: not enough food, not enough water, not enough firewood, children dying from dysentery and smallpox…and where was all that fabled gold?

Patience, Carleton urged. The Navajo could still thrive at Bosque Redondo. “Through all the clouds that now seem to surround this important, and, to them, vital matter, I hope soon to see some encouraging light,” he wrote.

Time was running out. Outcry was growing over the treatment of America’s first nations, not just in New Mexico Territory but throughout the West. Newspaper reports of the Sand Creek Massacre, in which U.S. troops attacked Arapaho and Cheyenne families in their sleep, jolted readers across the country.

In March 1865, the Senate and House passed a joint resolution “directing an inquiry into the condition of the Indian tribes and their treatment by the civil and military authorities of the United States.” Within weeks, army commanders in New Mexico learned that the inquiry was coming to them. Representative Lewis Ross, an Illinois Democrat, was traveling to Bosque Redondo to hold Congressional field hearings. And Herrero Delgadito, the blacksmith turned counterfeiter, would be among those called to testify.

The Condition of the Indian Tribes

Captain Henry Bristol didn’t mention the counterfeiting operation. One month after finding another three hundred duplicates of the tin ration tickets, he appeared before a team of Congressional investigators at Fort Sumner and swore that the blacksmith’s shop was an example of how well things were going at Bosque Redondo.

“The young men and boys seem very anxious to learn, and show much aptitude for the work,” Bristol testified at the June 1865 field hearing. “They have some blacksmiths among them who make good bits; one presented, made by a Navajo, is in the Spanish style.”

Bristol did his best to counter the camp’s growing chorus of critics. He allowed that there had been some deaths—exactly how many, he couldn’t say—but he described the prisoners as a largely contented and industrious lot. “If nothing interferes to prevent the present crops from maturing, as they now promise well, I think we shall raise nearly enough to feed the Indians until next season,” Bristol said.

Congressman Lewis Ross invited the prisoners to furnish witnesses of their own. The Mescalero Apache leader Cadette spoke first, telling Ross that the prisoners wanted just one thing: to go home. They had tried to make a life for themselves at the Bosque, but the people were always hungry. Dysentery, smallpox and measles claimed new victims every week. “About six days ago, four died: an old man, middle-aged man, a boy, and a girl,” Cadette told Ross.

The Diné chose Delgadito to speak on their behalf. He confirmed everything Cadette had said—the deprivation, the disease. By then, Delgadito had lost five of his own children.172 A clerk wrote down Ross’s questions, followed by Delgadito’s answers, as translated by an interpreter:

Question: Is there plenty of wood on the reservation for fuel?

“There is plenty below here, but we have to go too far for it. Don’t know whether fuel could be floated down the river or not; knows of some floating down; could pack the wood if we had the burros. The water has alkali in it, and they are afraid it will make them sick; a good many have been sick and died; when they drank the water, they took sick and died; and others have got sick by carrying mesquite so far. Those that were attended by the doctor all died; do not know his name; he was physician at the hospital. There is a hospital here for us; but all who go in never come out. We have physicians among ourselves, but they can’t cure all; some must die. They commenced to get sick about last October, and since then every day some of them have died; so many of them dying they are getting frightened; a good many of his children and grandchildren have died; three sons and two daughters have died; they are dying as though they were shooting at them with a rifle.”

Question: Do the young men like to work and want to work?

“Yes; the young men work well; love to work; even the women.”

Question: Are your women and children all pretty well now?

“All are not well; some of them are sick (all agree to what Herrero says).”

Question: If your people had plenty of wool could they make all the clothes?

“Yes; if we had the wool we could make all the clothes for the tribe. All of them know how to cultivate by irrigation; thinks there is plenty of land; but somehow the crops do not come out well. Last year the worms destroyed their crops.…There is plenty of pasture for all their stock; some have but 25, 30, or 40, but more have none; none have a hundred. They try and keep their sheep for their milk, and only kill them when necessary, when the rations are short or smell bad. They depend on the milk of the sheep to live and to give to the little children; they are honest and do not kill each other’s sheep; they own their animals themselves, and not in common; they would like each man to have his own piece of land and work it for himself and his family; they have not grain, stock, and other things enough; when they have enough they would like to have their children go to school; they would not like to have their children go to school until they had learned all kinds of trades, so they could make a living. Some officers at Fort Canby told them when they got here the government would give them herds of horses, sheep, and cattle, and other things they needed, but they have not received them; they had to lose a good deal of their property on account of the war, and the Utahs stole the rest from them; have been at war with the Utahs nine years, and about the same number of years with the Mexicans. Before the war with the Utahs and Mexicans, had everything we wanted; but now have lost everything. Herrero was quite young when the war commenced with the Mexicans. In the war everything was stolen on both sides, women and children, flocks. When children were taken we kept them, sold them, or gave them back. The Mexicans got the most children…”

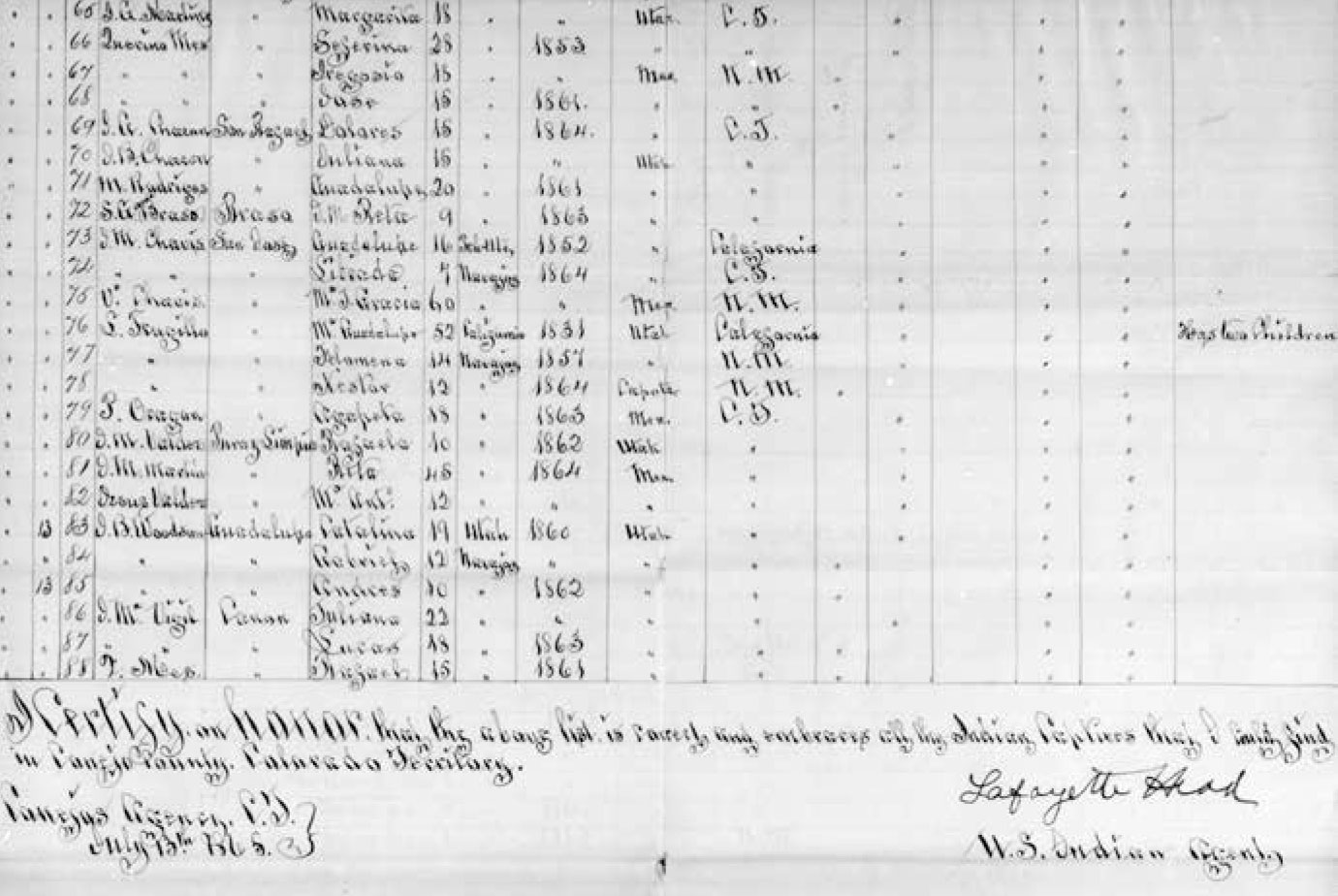

Ordered to compile a list of slaves in his jurisdiction, U.S. Indian Agent Lafayette Head omitted those he personally held in captivity. Fort Garland Museum.

“…we have only two, and they don’t want to go back; have not been in the habit of selling our own children; don’t know of an instance. They don’t expect to be rich again; but if they had plenty of stock, and wagons to haul their wood, they would prosper again. Some of the soldiers do not treat us well. When at work, if we stop a little they kick us or do something else; but generally they treat us well. We do not mind if an officer punishes us, but do not like to be treated badly by the soldiers. They say their women sometimes come to the tents outside the fort and make contracts with the soldiers to stay with them for a night, and give them five dollars or something else; but in the morning take away what they gave them and kick them off. This happens most every day. In the night, they leave the fort and go to the Indian camps; the women are not forced, but consent willingly; a good many of the women have the venereal disease. It has existed among them a good many years in their own country, but was not so common there as it is here; there are remedies to cure the disease, but they cannot get them here; they have no confidence in the medicines given them at the hospital; think it would do them no good; most of the old men know how to cure the disease; they use the root of wild weeds that do not grow here; some of the people are dying here of the disease; some were taken to the hospital, but were not cured; when they find out a person has that disease they report it to the hospital; this they have done for some time; but all they have reported there have died. The custom of the tribe is never to enter a house where a person has died, but abandon it. That is the reason they don’t want to go to the hospital; they would prefer a tent out by their camps for a hospital.”

By Mr. Ross to Herrero, Question: Were you made a chief by your own people or by the whites?

“By my own people.”

To the chiefs, Question: Would you all like to go back to your old country or remain here?

“They would rather prefer to be in their own country, although they have most everything they want here; they are all of this opinion, and would like to have you send them back; and if you have any presents to give them they will distribute them among them. If they were sent back they would promise never to commit an act of hostility.”

Question: If you are sent back could you make your own living?

“Yes; we could support ourselves; and you could send some troops to see that we kept our promise.”

Finally, Ross got to the big question, the only one the Diné really cared about:

Question. Do you want us, when we go back, to tell the Great Father and the great council that you would like to be sent back to your old country?

“Yes; we would all like to go, and if sent back would go straight back the

way we came.”

Question: Are the soldiers treating you badly? And if so, let us know.

“The soldiers about here treat us very bad—whipping and kicking us.”

Question: Do you get enough to eat here?

“We do not get enough to eat.”

Question: How much do you get as a ration?

“(No answer recorded)”

Question. Is there any game in your own country?

“Yes; there is plenty of rabbits, antelope, deer, and wild potatoes. Herrero says they would like to have you send them back to their own country. They think you are the greatest men and can send them back, and they would like to have it done soon.”

Ross explained that he and his colleagues didn’t have the authority to release anyone—they could only relay the wish to the president and Congress. Delgadito conferred with other Diné headmen and then turned to the interpreter. “They say they will try and work to do all they can to support themselves until they learn what disposition is to be made

of them.”

Delgadito had one other request that day. He told Ross that his name— Herrero—meant “blacksmith.” He explained that he’d been training some of the other men, teaching them how to fashion bridle bits, hatchets and such. Was it possible, the counterfeiter asked the congressman, to send more tools for the blacksmith’s shop?