Official SWAIA Artist Policies

Official SWAIA Artist Policies

Statement on Artist Policies

These Official SWAIA Artist Policies (“Artist Policies”) are applicable to all artists who apply to and/or participate at the Santa Fe Indian Market (“Indian Market” or “Market”). Participation in Indian Market is a privilege, not a right. These policies have been implemented in order to protect both the artists and the organization. These policies will also be published on the SWAIA website. Please read them carefully and print them out for your records.

SECTION 1 | APPLICATION POLICIES

1a. Applications

To be considered as an exhibitor at Indian Market, you must have completed the Indian Market Application and submitted all images and required documents and paid any and all applicable fees by the deadline stated on the application which is available from the SWAIA website. Any applications received after the late deadline for any reason, will NOT be considered for the summer Indian Market. Artists who submit a hard copy application by mail should include signature confirmation or send via certified mail to ensure that SWAIA receives the application. SWAIA is not responsible for lost or misdirected mail.

1b. Eligibility

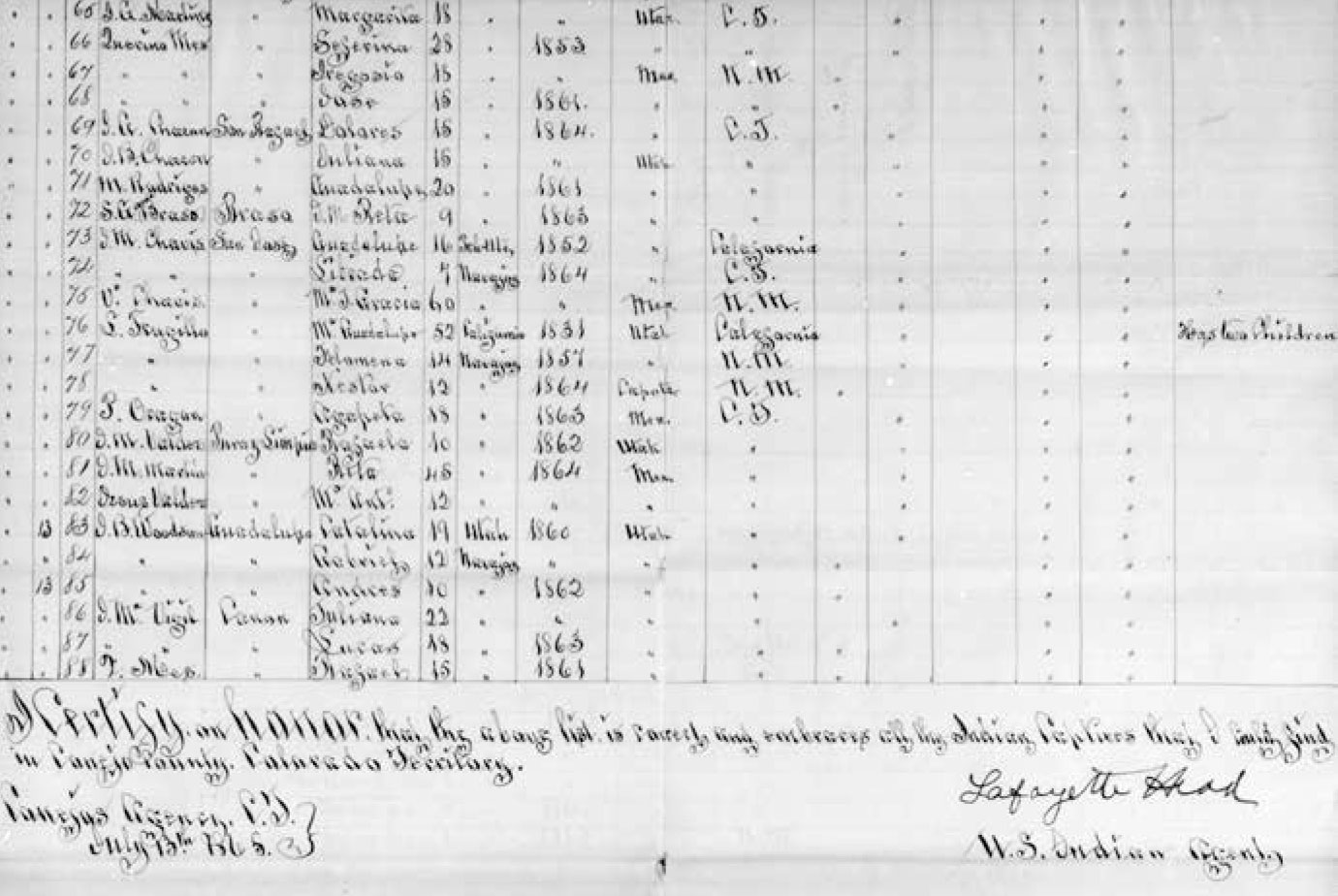

Applicants to Indian Market must be enrolled members of a United States or Canadian federally-recognized tribe or Alaskan Corporation, and must submit proof of enrollment in the form of a legible copy of the applicant’s enrollment card, a Certificate of Indian Blood (CIB), Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood (CDIB), or a Secured Certificate of Indian Status Card (CIS/SCIS) (Canada). The enrollment number must also be included on the application form.

1c. Tribal Certification

Artists who do not have a CIB/CDIB/CIS/SCIS or official tribal enrollment card can provide a tribal certification from a federally recognized tribe. However, SWAIA will review documents used as proof of Native standing and have sole discretion of accepting documents for Market eligibility. If your enrollment is pending, you may apply and indicate such. However, if your status is not confirmed by Jury time, you will be disqualified from participating.

1d. Jurying Process

SWAIA typically selects three (3) jurors per classification who are experts and/or have much experience with the classification they are jurying. These jurors review

the images artists submit with their application and each juror assigns a total of 100 points each, in 4 criteria areas. The totals are then calculated for a maximum possible score of 300 points. The four criteria are: Technical Execution, Concept/Design/Creativity, Aesthetics, and Indian Market Standards.

In some classifications, the sheer number of applicants, and the diversity of the forms warrants a different jurying pool strategy. SWAIA might adjust the pool to stay efficient in processing applications. An example of strategies to manage large groups are (1) when Jewelers that work primarily in stones and shells in Division B and Division D have to be juried separately from the rest of Jewelry; and (2) when Sculptors who work primarily in fetishes/miniature sculptures as found in Division C are juried separately from the rest of sculpture.

1e. Juror Selection

Jurors for the application process are selected from individuals who have long time expertise or knowledge in each classification. These individuals traditionally include accomplished and long-time artists, museum curators, experienced collectors, and art educators. Jurors with potential conflicts of interest are avoided; for example, a gallery owner that deals in Native Sculpture would not be selected as a juror for sculpture. Jurors may generally change every year, or a juror may not jury the same classification two years in a row but may jury another classification in which they are an expert. SWAIA favors Jurors who can provide credibility, integrity, and artistic literacy to the jurying process.

1f. Admission, Waitlist, and Unacceptance

Admission into Indian Market is based solely on the weight of the artist’s work as submitted in their application images. Scores are tabulated and then organized based on highest scores to lowest. Artists are assigned admission and a booth with the highest scores in each classification being assigned first. The number of assigned booths from each classification is based on the NUMBER OF APPLICANTS.

For example: The first top scoring 20% in each classification are assigned in the initial assignments of booths. Each classification has a set number of assigned artists based on the number of applicants that will vary as each classification has varying numbers of applicants. If 400 jewelers apply, the top scoring 80 artists (20% of 400) will be initially assigned booths whereas in Textiles, a class in which typically only 65 artists apply, 13 artists (20% of 65) will be assigned.

This is applied across all classifications and is the fairest way of admitting artists into market, based on total applications in each classification. SWAIA then assigns another 15% across all classes, another 15%, then 10%, etc., until there are no

longer any available booth spaces. This creates the cutoff between accepted artists and waitlisted artists.

Waitlisted artists: Waitlisted artists are artists whose work is acceptable, but for whom there is no space initially. Approximately 80 to 120 artists each year drop out before Indian Market each year. SWAIA then moves through the waitlist to fill those spots. The waitlist is ranked in the same manner as accepted artists, based on score and based on the percentage of applicants in that classification. Waitlisted artists are contacted according to their scores and must be ready to pay their booth fee. Artists can sell out early, sometimes within minutes, which opens booth locations around the market. If an accepted artist misses their payment deadline, they will be removed from the accepted artist list and moved to the end of the waitlist. If a waitlisted artist is unable to pay their fee at the time of contact by SWAIA, they will not be removed from the waitlist, simply moved to the end. Please stay ready to participate.

1g. Artist Inquiries and Appeals Process

Our “Frequently Asked Questions” section of our website holds answers regarding the jurying process, juror selection, and the criteria for jurying. Artists may start there and if there are further questions, please send an email to artistservices@swaia.org.

Artists are always welcome to schedule in-person meetings regarding the jurying process, individual scores, and/or any concerns. We schedule blocks of time for appointments to honor all meeting requests, but we usually have a large volume

of requests immediately after Acceptance letters are mailed. Please be patient if your meeting is scheduled a week out or longer because we have a small staff, and those meetings will be made in the order the requests are received.

1h. Booth Assignments and Booth Standards

Booth assignments are at the complete discretion of SWAIA. SWAIA will try to accommodate booth requests to stay in the same place or move to a new location, but booth assignments are based on jurying score. Booths are assigned based on score, from highest scores to lower scores until there are no available booths. SWAIA goes to great lengths to ensure accuracy in the official Booth Guide as well as the mobile phone app, but please be aware that artists must also assume some personal accountability to inform their clients of any change to their booth location.

Booth Standards: Each Market artist paid for a specific booth space/size, and SWAIA will honor this arrangement with all Market artists. All supplies, inventory, and displays must be contained inside of the booth. No build outs can extend from the booth; this include fashioning overhangs and tying tarps to

surrounding buildings. SWAIA Standards Monitors will be checking sidewalks, roads, and grassy areas for foot traffic obstructions as well as trash left after load out. If SWAIA staff sees that you have left trash behind, you will be notified that

there will be a $250 non-refundable cleaning fee applied to your next year’s application. Entry into market will not occur until trash deposit is paid in full.

Booth Panels: Free-standing grid back panels with footing are required in booths along Lincoln where merchant stores are located (currently 739-762, though numbers are subject to change). Net or mesh sidewalls should not prevent visibility through the booth. Your letter of Acceptance will notify you if your booth will have that restriction.

1i. Payment and Refund Policy

Application and Booth payments must be paid by the deadline as outlined in the application and artist packets. No exceptions will be made for any reason, unless the error lies with SWAIA. The burden of proving that it is SWAIA’s error lies with the artist. Artists must retain proof of submission of their payment either through copies of receipts, mailed payments, photos, etc. If it is SWAIA’s error SWAIA will do their best to make the error right.

Please be aware of the refund deadlines printed in the Acceptance Letter. For example, a Full Refund (minus $50 Administration Fee) four months before Market date, Half Refund (Minus $5- Administration Fee) three months before Market date, and No Refund two months before Market date. The amount refunded reduces as the Indian Market gets closer. There is absolutely no refund for the artist application fee.

SECTION 2 | GENERAL RELEASE/EXHIBITOR DECLARATION AND LEGAL POLICIES

2a. General Release/Exhibitor Declaration

Any Native American artist wishing to participate at the Santa Fe Indian Market must complete and submit a hardcopy or online, the official SWAIA application, required documents, and applicable fees, by the deadlines noted in the

application. The application must also be signed and dated by the exhibitor applicant, who agrees to the following, as outlined in the Exhibitor Declaration:

I attest that: I am the artist and that all artwork submitted by me is a true and accurate representation of my work to be sold at the SWAIA Santa Fe Indian Market. I am an enrolled member of a United States or Canadian federally recognized

Tribe/Band/Corporation.

I understand by signing this application: I agree to abide by SWAIA’s Indian Market Standards and Artist Policies, including but not limited to all work being made by me, or

in the case of Full-Time Collaborators, by my collaborator and myself. I agree to all SWAIA decisions and procedures regarding the application process, participation, and booth assignment at Indian Market. I agree to authorize SWAIA to create and submit a City of Santa Fe Special Event License Application (SELA). I will abide by the rules set by that SELA and State of New Mexico Tax and Revenue Department regarding any and all fees and taxes. I agree that submitted images can be used by SWAIA for any and all promotional material or other usage deemed necessary by SWAIA. I understand that any misrepresentations of my enrollment status, my artwork or non-resolution of legal action against SWAIA will disqualify me from participating in Market.

An application must be signed by the potential artist/exhibitor, either with signature or an electronic signature. An application submitted without a signature will be considered incomplete and will not move forward to the jurying process. All artists should retain photocopies of their application for their records.

SECTION 3 | BULLYING AND NEGATIVE INTERACTIONS WITH SWAIA STAFF AND BOARD

3a. Bullying

SWAIA has a zero-tolerance policy for bullying of staff or Board Members. SWAIA defines Bullying as verbal or physical abuse, threats of violence, aggressive behavior, behavior meant to intimidate, harass berate, ridicule, or by willfully ignoring instruction.

3b. Market Acceptance

An artist who has participated in Indian Market or has applied for inclusion for this year’s Indian Market, they will jeopardize their acceptance if they abuse defame, slander, or otherwise denigrate SWAIA, the Santa Fe Indian Market, and/or other Indian Market artists.

3c. Violations

An artist who is found to have violated the above policy (Section 3) will be notified, verbally and/or in writing. The violation will be recorded with Artist Services, and the artist will forfeit their participation at Indian Market for a period determined by the SWAIA Executive Director. An artist may appeal the decision to the SWAIA Board, in writing, within 30 days after the notification of violation and forfeiture was received.

SECTION 4 | SWAIA STANDARDS AND VIOLATIONS

4a. Jurying Process

During the jurying process, jurors may find violations of the official SWAIA standards manual in the images submitted with the artist application. Artists are

responsible for knowing the standards applicable to every classification for which the artist applies. Ignorance of the standards is not a defense.

A violation of the standards during the jurying process will result in a deduction for that image only determined by the jurors of that classification. Deductions may be slight, if the violation is only a small part of the overall piece, or the deduction may be a total disqualification if the total piece is a violation. Jurors will still award a score on the other two images submitted. Violations will be noted in the notes section of each juror’s scorecard.

4b. Prohibited Activities

Selling another artist’s work: Artists must only sell their own work at their booth, unless the artist is sharing a booth with another artist who has also been juried into Market. This includes the work of other family members. For example, an artist who has been successfully juried into Indian Market in the category of pottery, may only sell his or her pottery and not that of other family members not juried into Market.

Submission to Best of Show competition only in approved classifications: Artists may only submit for judging of work in the classifications for which they have been accepted. For example, an artist who has been juried into Indian Market in the classification of jewelry may only submit jewelry for judging, and not pottery, textiles or baskets.

4c. Enforcement of Artist Policies, Violations during Market

The enforcement of Market Standards and Booth Standards are intended to help guide and protect our hardworking artists and their customers/clients.

Direct Observation by Standards Monitor: We will have Standards Monitors (SM) and secret shoppers observing the market event for items that do not meet SWAIA standards. The SMs are responsible for identifying booth issues, issuing violation forms, and informing the Artist Services Coordinator (or Executive Director) when violation forms are written. The violation form process is as follows:

1) the initial acknowledgment that there are SWAIA Market Standards and Policies is when the application is signed, and by signing that you will abide by both the Indian Market Standards and Artist Policies there is confirmation of knowing the requirements;

2) if an SM fills out a violation form with instruction for the assigned booth artist to sign the violation form and to remedy the issue. The artist’s violation will be connected to the next Market application causing a review of the noted violation, which may affect future participation in SWAIA events.

3) If there is a refusal by the artist to sign their name on the form, then the artist must pack up and vacate the booth; no refund will be given. The artist will no longer be allowed to apply for or participate in future Market events.

4) two consecutive written violations in the same year will result in a one-year exclusion from future SWAIA Markets. All write ups will be cross referenced to assist placement, enforcement, and when reviewing appeals.

Reported Violations to Standards Monitors: We will investigate complaints and concerns regarding market and booth standards violations and observe the situation directly.

Reevaluation to ensure continued compliance: Even if the artist feels that the violation is in error, he or she must still abide by the SWAIA staff/representative’s decision to withdraw the piece(s). Failure to abide by this decision may result in immediate expulsion from Indian Market and potential banishment from future Indian Markets. Violation will be noted on the official SWAIA form and

photographs taken for Artist Services.

4d. Appeals process:

If an artist feels that the violation/withdrawal decision was made in error, they must document the pieces through photographs, written descriptions, witness testimony etc. Artists may then initiate the appeals process AFTER Indian Market by writing an appeals letter to the SWAIA Executive Director. Please include photos and a description of the pieces and why you, the artist, feel that the violation was in error. The Executive Director will then advise you, in writing, of their decision and the next step(s), if necessary.

SECTION 5 | EXHIBITORS THREATENING AND/OR ENGAGING IN LAWSUITS/LEGAL ACTIONS

5a. Rights

Artists and/or potential exhibitors are within their rights to engage in the legal process in accordance with applicable law. SWAIA reserves the right to suspend the artist’s/potential exhibitor’s participation at Indian Market until the legal dispute is resolved to the satisfaction of SWAIA.

5b. SWAIA Response and Legal Policy

SWAIA reserves the right to vigorously defend itself against any and all claims. SWAIA will seek compensatory damages for claims brought with the intent of harming or otherwise disparaging the SWAIA brand, organization, Board of Directors, Staff or other artists participating at Indian Market.

5c. Participation at Indian Market

Participation at Indian Market is a privilege, not a right. Fundamental fairness in the jurying process, booth assignments, PR/Marketing, and Awards program are guiding principles of SWAIA; regardless of tribe, age, gender, art form, and/or duration of time participating at Indian Market.

5d. Agreement to Abide by all SWAIA Policies and Decisions

By completing and signing the SWAIA Application, artists and vendors agree to abide by all SWAIA policies and decisions regarding the selection/jurying process, booth assignments, and general participation requirements and logistics of Indian Market.

SECTION 6 | ART DONATION POLICIES

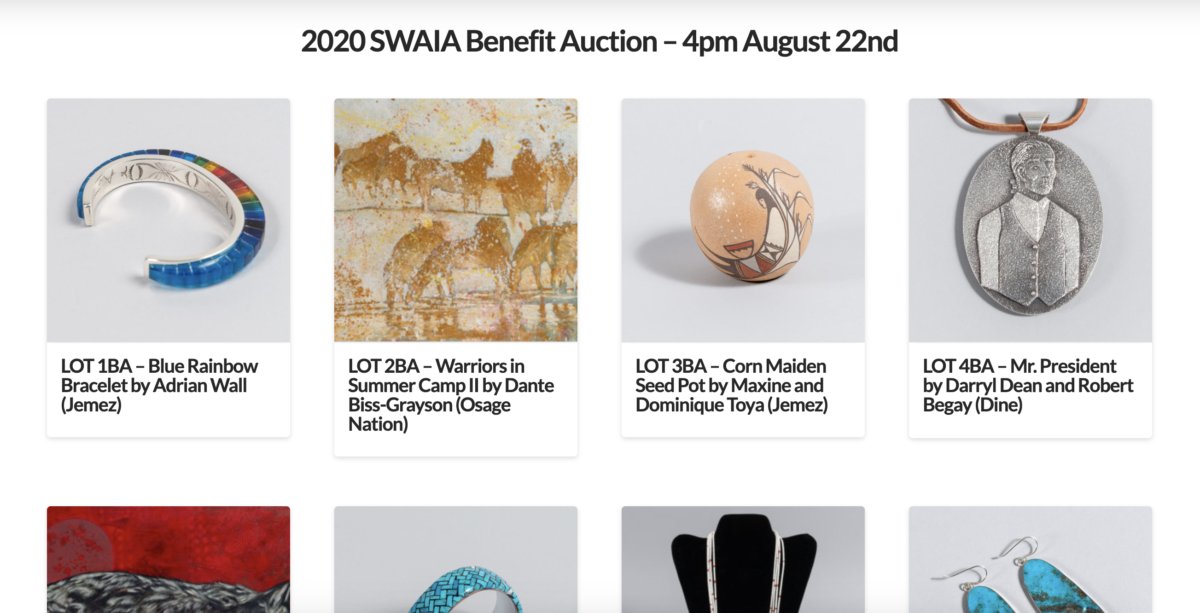

6a. All donations of art, whether by the original artist or the owner of said piece, become the sole property of SWAIA to be used in any manner that SWAIA deems fit. The donor, in making the donation, guarantees that the donated art piece is the property of the donor or artist and is free from any liens, claims, encumbrances, does not infringe on any copyright, and is given without any expectation of performance or compensation by SWAIA staff or board.

6b. Donor/artist further agrees to grant SWAIA an unlimited release of any images of the donated piece to be used by SWAIA for PR/Marketing and promotional purposes, in perpetuity.

SECTION 7 | ARTIST AWARDS PROGRAM POLICY

The SWAIA awards program recognizes and rewards artistic excellence and technical expertise in the many classifications of Indian Market. Artists are awarded ribbons and cash awards in the Classifications, Divisions, and Categories as outlined in the Standards Manual. The award amounts may vary at the discretion of SWAIA and are namely contingent upon the funds raised and available for the SWAIA Awards Program in any given year. Therefore,

cumulative awards are NOT guaranteed. (For example, if you win Best of Division, you may not be also paid out for Best of Category.)

SECTION 8 | FOOD VENDORS/NON-PROFIT PARTICIPANT POLICIES

Food Vendors and non-profit participant policies are generally bound by the same policies as artist vendor participants, as applicable. The application process, selections, booth assignments and locations, and fees are all at the discretion of SWAIA. Participants under these categories agree to abide by all decisions of the SWAIA staff.